- Home

- John Livesey

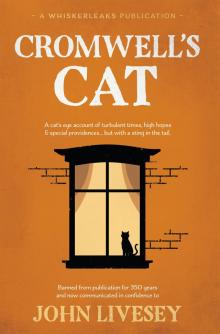

Cromwell's Cat Page 21

Cromwell's Cat Read online

Page 21

MAJ

“Yours, Tomkins, and you keep dreaming it but it’s best now you stop tapping and let Crumb rest in peace.”

TOMKINS

“I will, Maj. I will, when he’s got back to me.”

MAJ

“He can’t get back to you. You heard him – his last words: ‘Ninth chapter; ninth life – no more’ Can’t be much clearer than that, can it?”

TOMKINS

“No… but I’ll keep tapping. After all, if I stop, the eels will stop slapping his face and he’ll have nothing to ask his astrologer.”

MAJ

“I suppose that’s true but I doubt he’ll need an astrologer where he’s gone.”

TOMKINS

“Meaning?”

MAJ

“Well, if he’s gone to the other place an astrologer won’t help. And if he makes it up here, which I fully expect…”

CRUMB

“I’ll be able to ask the Lord himself, won’t I, Majesty?”

MAJ

“Of course you will. There, you see, Tomkins, even the Lord Protector agrees. What?! General Cromwell!?”

CRUMB

“The same. Transported hither on a carpet of dreams. Thanks Tomkins for not listening to them. The dream is alive and, in it, so are we – you in your world, me in mine until you can join me here – and Tomkins…”

TOMKINS

“Yes?”

CRUMB

“Fens, eels and decoy ducks – it is. Just the ‘place of rest’ we were looking for. You’ll love it.”

TOMKINS

“I knew it. Should I stop tapping now?”

CRUMB

“Yes, stop tapping. Have a good ninth life – what’s left of it. See you soon. Now, Majesty, show me where to find the parliament.”

MAJ

“Down there. Can you see – the Thames, Spring Gardens …”

CRUMB

“Yes.”

MAJ

“Westminster Palace Yard?”

CRUMB

“Oh yes, I see – Westminster Hall – and the parliament house. And the parliament due to meet any time now and put the top-stone to the work of settlement whereby God will own His people in the eyes of the world. Come on, Majesty. Let’s watch. This could be good!”

Appendix

Some Important Events…

The Self-Denying Ordinance

…was passed by the Parliament of England on 3 April 1645. Under its terms all members of the Long Parliament who were also officers in the Parliamentary army or navy were to resign either their Parliamentary seat or their military commission. This followed the creation of the New Model Army by another ordinance, passed on 15th February. Cromwell duly resigned his commission but in the run-up to the crucial Battle of Naseby (14th June 1645) he was exempted from the terms of the Self-Denying Ordinance at the special request of Sir Thomas Fairfax, C-in-C of the New Model Army, to fill the vacant post of lieutenant-general of the horse.

The first ‘Agreement of the People’

…drafted by leading Levellers & representatives of rank and file soldiers (known as ‘agitators’) & presented to the General Council of the Army at Putney in October 1647. It proposed a new constitution for a newly ‘free’ nation (the defeat of the king in the First Civil War being held to signify the end of the ‘Norman Yoke’ dating from the Conquest in 1066) and declared the people to be sovereign and their representatives in parliament to have full power to make laws, appoint officers of state, and to declare war and make peace. Parliaments were to be biennial and constituencies reapportioned according to the number of inhabitants with no mention of a property qualification. Nor was mention made of King or lords. It also introduced the idea of certain ‘fundamentals’ reserved to the people themselves, which it would be beyond the power even of parliament to alter. These included freedom of religion and total equality before the law.

The Vote of ‘No addresses’ (17/01/1648)

…marked the end of the road for attempts by parliament and army to reach an accommodation with Charles I. His escape from Hampton Court (11th November 1647) and flight to Carisbrook in the Isle of Wight carried the clear implication that his mind was elsewhere as became clear shortly after. On 24th December the parliament presented him with four bills setting out their minimum conditions for the renewal of negotiations These included parliamentary control over all armed forces for the next twenty years and the annexed suggestion that episcopacy be abolished and the book of common prayer banned. Charles was given four days to reply but chose instead to sign an engagement with commissioners from Scotland by which they agreed, if necessary, to send an army into England to restore him to his just rights. He rejected the ‘Four Bills’ and attempted to escape by sea. He failed; his guards were redoubled and the Commons passed the Vote of No Addresses on 3rd January 1648 to be followed by the Lords a fortnight later.

Pride’s Purge (06/12/1648)

…members of parliament arrived to find the building surrounded by several regiments of horse and Colonel Thomas Pride at the entrance to the Commons with a list of members to be excluded and Lord Grey of Groby at his side to help identify those on the list. This included those who the day before had voted the terms agreed between the king and parliament’s commissioners at the Treaty of Newport to be sufficient ground for proceeding to a settlement, and all who the previous August had refused to declare the Scottish invaders to be enemies and traitors. Of those excluded fortyfive were arrested and forced to spend the night in a Westminster tavern known as ‘Hell’. Twenty of these were released before Christmas. Many more members voluntarily absented themselves to register their disapproval of the violation of parliamentary privilege. The event came to be known as ‘Pride’s Purge’.

Blackfriars

The church of St Anne, Blackfriars

… was built on the site of the monastery of the Dominicans or ‘Black Friars’ dissolved by Henry VIII. By the 1650s it had become a centre for radical puritanism, the ‘Fifth Monarchists’ (See Thomas Harrison below) in particular. Preachers there (including Christopher Feake, Vavasor Powell & John Rogers) hammered home the theme that the last times foretold in the bible (eg the books of Daniel and Revelation) had arrived and it behoved true believers to do all in their power to bring in the ‘Rule of the Saints’. Thus, when Cromwell expelled the Rump he was compared to Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt, but when he became Protector, the same preachers identified him as ‘the little horn’ (Daniel 7) that shall make war on the saints (Christopher Feake) and as ‘a vile person to whom they shall not give…the kingdom, but he shall come in peaceably and obtain the kingdom by flatteries’ (Daniel 11.21. Vavasor Powell).

…And Personalities.

(in alphabetical order)

John Bradshaw (1602-1659)

Convinced republican, friend of John Milton and Chief Justice of Chester & North Wales, chosen to preside over the High Court of Justice for the King’s trial as the most senior judge willing to serve (all judges of the central courts having declined the offer). He also presided over the High Court set up to try leading royalists and in March 1649 was named as president of the Council of State (a post he held until November 1651 and again from January 1653). In September 1654, returned as a member for Staffordshire to the first Protectorate

parliament, he refused to sign the recognition required of the government ‘as it is settled in one single person and a parliament’ and so was not allowed to take his seat. He died in 1659 and was buried in Westminster Abbey, only (along with Cromwell & Ireton) to have his remains dug up at the restoration, hanged at Tyburn and his head impaled on a spike and displayed in Westminster Hall

Thomas, Lord Fairfax (1612 – 1671)

From a prominent Yorkshire family, rose to prominence as lieutenant-general of horse in the northern army. In 1645 on the formation of the New Model Army he was appointed Commander-in-Chief (a ‘political’ appointment in that his fame was from the battlefield and he was not closely associated with any political faction). In the years that followed he firmly aligned himself with his soldiers’ grievances but largely held aloof from their political aspirations. This culminated in 1649 when, named as one of the commissioners on the High Court of Justice for the king’s trial, he attended their first preliminary meeting but when his name was read out on the first day of the trial (20th January 1649) a lady (allegedly his wife Anne) called out from the gallery that ‘he had more wit than to be there’. He never appeared thereafter. In June 1650 he resigned his commission rather than lead the army on its invasion of Scotland. Cromwell took his place. In the years that followed he stayed out of politics but opponents of the regime (royalists in particular) never lost hope and in 1659 he led the Yorkshire gentry in support of General Monk on the way to the restoration of Charles II.

Sir Arthur Haselrig (1601-1661)

Parliamentarian and notable opposition figure in the Long Parliament from its early days. In 1645 he supported the Self-Denying Ordinance and the creation of the New Model Army and then took the army’s side in the confrontation with parliament in 1647. Appointed governor of Newcastle, his duties meant he was absent for Pride’s Purge and the king’s trial but he became a leading member of the Rump over the next four years. In February 1653, with the army demanding action and a crisis clearly threatening, Haselrig took control of the ‘Bill for a New Representative (parliament)’, with the aim at last of asserting parliamentary sovereignty. Cromwell’s expulsion of the Rump on 20th April 1653 prevented this but for Haselrig no power could dissolve the parliament but themselves and no settlement would be achieved without them. He held to that view throughout the protectorate and only realised how wrong he’d been in 1659 when he and the re-called Rump failed so disastrously. A conviction politician but also one with a reputation for taking advantage of his position to enrich himself at others’ expense.

Thomas Harrison (1606 – 1660)

Army officer & religious radical, the leader in the army of the ‘Fifth Monarchists’. They took their name from the prophecy in the book of Daniel (Chapter 7) of four beasts (or kingdoms) that shall have their day before Christ shall come to reign (the Fifth Monarch) and his saints with him. ‘Saints’ they understood to be those like themselves, true believers, God’s chosen ones. They were also inclined to believe that the execution of Charles I marked the beginning of the end of the Fourth Monarchy and when Cromwell dissolved the Rump in 1653, that was seen as the last rites of the old order. Now was the time for the Saints to inherit the kingdom, except that not everyone agreed. The new experiment (Barebone’s Parliament), never quite what they looked for, failed and was replaced by the Protectorate – in their eyes an attempt to set up again what God had overthrown. They had no choice but to oppose it, as Harrison did for the next six years. At the restoration he was tried and executed as a regicide. He died convinced as ever that the Lord was working his purpose out and his death would change nothing.

Henry Ireton (1611-1651)

Radical puritan with legal training and from the early days of the civil war a close associate of Oliver Cromwell. They met at the battle of Gainsborough in 1643 and then, when Cromwell was appointed Governor of Ely, he secured Ireton’s appointment as his deputy. The next year he rose to be quartermaster-general in the Eastern Association army, where Cromwell was lieutenant-general and he supported him in his campaign for a ‘Self-denying Ordinance’ (See above) and the creation of the New Model Army. In 1646 he married Cromwell’s eldest daughter, Bridget. In 1647 again alongside Cromwell he was at the heart of attempts to craft a new constitutional settlement, which would respect rights while redressing grievances (the Heads of Proposals) and just over a year later he repeated the process in the Second Agreement of The People, presented to parliament on 20th January 1649 – only to be ignored. His was also the guiding hand behind ‘Pride’s Purge’ of parliament on 6th December 1648 and members’ resentment of this may explain their subsequent rejection of him for membership of the new Council of State. In August 1649 he followed Cromwell to Ireland, never to return. He died at Limerick in November 1651

John Lambert (1619-1684)

Soldier and politician, born in Yorkshire, he rose to prominence alongside Thomas Fairfax (see above) in the northern army. Supported the Self-Denying ordinance and the creation of the New Model Army and in 1647 joined Ireton in drawing up the Heads of Proposals. Took no part in the king’s trial, being engaged elsewhere. Accompanied Cromwell to Scotland in 1650 and played a crucial part in the victories at Dunbar (3rd September 1650) & Inverkeithing (20th July 1651). In the run-up to the expulsion of the Rump in 1653, Cromwell was reported as speaking of being pushed on by two parties (Lambert – referred to elsewhere as ‘bottomless’ – and Harrison) ‘to do that the consideration of the issue whereof made his hair to stand on end’. He also said (opening of Barebone’s Parliament 4th July 1653) ‘if I were to choose any servant… for the army or the commonwealth, I would choose a godly man that hath principles,…because I know where to have a man that hath principles’. That would apply to Harrison (see above), who was there to hear him. Lambert, absent having just withdrawn his support for reasons best known to himself, was harder to pigeonhole – hence perhaps ‘bottomless’. Later he was held to have orchestrated the end of ‘Barebone’s’ and he was the architect of the Protectorate. The constitution he devised in the Instrument of Government, widely seen as a move back to monarchy, was never intended as such but rather as a balanced constitution and a check on an overmighty parliament. The Petition and Advice, which followed in 1657, he opposed on just those grounds – that it was intended as a return to monarchy. As a result he was cashiered and retired to a private life until his brief and spectacularly unsuccessful re-appearance in 1659. Tried and imprisoned at the restoration, he remained a prisoner until his death in 1684

John Lilburne (1615 (?) – 1657)

Prolific pamphleteer, political radical (a leading Leveller) and anti-authority figure, from 1638-1655 Lilburne found himself (sooner rather than later) at odds with every government under which he lived. Widely known as ‘Freeborn John’, for him the quarrel was always personal, he standing up for individual freedoms against power and privilege (be it freedom of conscience in religion, or in business – for the small trader against merchant adventurers and monopolists). It was famously said of him: ‘If the world was emptied of all but John Lilburne, Lilburne would quarrel with John and John with Lilburne’. From 1640 he found a friend and protector in Cromwell and in 1644 supported him in his moves against the Earl of Manchester and for the Self-Denying Ordinance. In 1647, as one of the leading ‘Levellers’, he was among those behind the Agreement of the People presented to the General Council of the Army at Putney. In January 1649, when the second ‘Agreement’ was presented to and ignored by the Rump, an outraged Lilburne went on the attack. Tried for treason at London’s Guildhall (October 1649) the jury found him ‘Not Guilty’ – greeted with general acclamation and celebrated with bonfires. Early in 1652 he was condemned by the Rump for outspoken (but probably justified) attacks on Haselrig, fined £7000, banished and threatened with being tried as a traitor should he ever return. Following the expulsion of the Rump, he did return in May 1653 and was sent for trial at the Old Bailey. The case appeared open and shut but it seemed they’d forg

otten that this was John Lilburne. He questioned the original sentence delivered by an illegal parliament – and if it wasn’t illegal wasn’t Cromwell the more guilty than him in that he had expelled them in defiance of an act to prevent such offence? He even questioned whether he was the John Lilburne intended in the Act of Banishment – and at the end of a long trial the jury found him ‘not guilty of any crime worthy of death’. Again the verdict was greeted with universal acclamation – even the soldiers guarding the court joining in. Despite his acquittal, Lilburne was kept in custody and under the Protectorate transferred to Mount Orgueil in Jersey. He later became a quaker and died in 1657

Thomas Rainborough (1610 – 1648)

Colonel in the New Model Army who in 1647, from being among the deputation that first presented the Heads of Proposals, became so disaffected with Cromwell and Ireton’s on-going attempts to address the king’s reservations, that at Putney he emerged as a leader of those arguing instead for the Leveller-inspired ‘Agreement of the People’. Celebrated down the centuries for his assertion: ‘the poorest he that is in England hath a life to live as the greatest…Every man that is to live under a government ought first by his own consent to put himself under that government.’ He was murdered a year later by a group of royalists5 at the siege of Pontefract in a kidnap attempt gone wrong. London Levellers turned out in force for his funeral (reportedly 3000 in the procession) and his sea-green colours became those of the movement as a whole

Cromwell's Cat

Cromwell's Cat